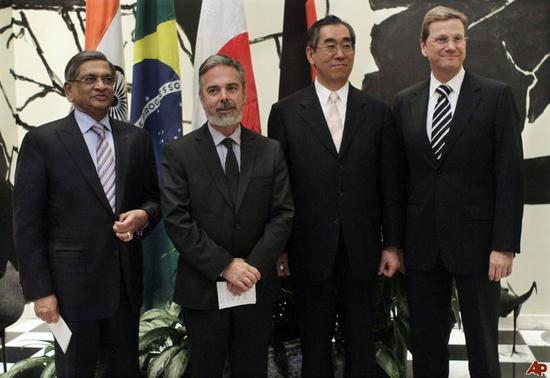

The G4

David Bosco recently wrote an interesting post about UNSC reform, arguing that Russia and China are far more instrumental in blocking reform than is generally thought.

Discussions about UN Security Council reform have existed since the UN’s inception, yet they have taken place in their current form for around two decades, without much progress. An amendment of the UN Charter requires a two-thirds majority in the General Assembly, which has been complicated due to sharp divisions between those who want new permanent seats (G4) and those who prefer new elected positions (a group called “Uniting for Consensus”). This has made it easier for Russia and China, the two BRICS members with a permanent seat, to avoid adopting a firm position when pressed by the three BRICS countries that seek admission to the UNSC – Brazil, India and South Africa.

Yet while Great Britain and France are generally more open to reform, policy makers in the United States, China and Russia are thought to oppose it. Russia and China are undoubtedly most critical, being the only P5 who have not explicitly supported any BRICS’ individual candidacy. While Britain and France have supported Brazil’s bid, the United States supports India’s position.

It would thus not be exaggerated to say that the BRICS’ positions are squarely opposed regarding UN Security Council reform, and there is no sign that this has changed since 2006, when the BRICS began to slowly institutionalize.

Russia’s reluctance to reform the UNSC can be explained by its fear that an expansion of permanent UNSC voices might diminish its influence. This sentiment is particularly strong since P5 membership is, aside from its nuclear capacity, Russia’s only basis for global power status. Russia could calculate that the entry of Brazil and India may help counterbalance the West or even China, of which Russia remains distrustful. Yet Russia is too uncertain of how exactly new permanent Council members would behave to fully support their claims. Simply put, the potential cost for Russia of any change to the status quo is too high, while potential gains are merely moderate.

A similar logic applies to China, even though, in the case of global momentum in favor of reform, China would not want to be seen as a principal obstacle in adapting the UNSC to 21st century realities. China may be unconcerned about a stronger representation for Brazil, and even Beijing’s worry about India may be smaller than is generally assumed. Yet G4 reform would also bring Japan into the Council permanently, a move to which China remains strongly opposed.

Policy makers and analysts in Tokyo are keenly aware of this. A considerable number of scholars I spoke to during a recent visit to Japan were markedly unenthusiastic about dedicating time and energy towards pushing for UNSC reform. Few had taken notice of Brazilian Foreign Minister Patriota’s recent article in Project Syndicate arguing for the ‘globalization of the Security Council’. Compared to thinkers in Germany, India and Brazil, Japan’s desire to obtain permanent UNSC membership currently seems to be eclipsed by more immediate regional security threats.

What does that mean for decision makers in Brasília? At first glance, one may conclude that Russia’s and China’s opposition to reform implies that the BRICS grouping should play no role in Brazil’s strategy. Yet engaging Moscow and Russia must be a crucial component of building global consensus. At the same time, the IBSA grouping will inevitably be an important vehicle, given that both India and South Africa share Brazil’s goals.

Brazil faces a fiendishly difficult paradox: Its candidacy is perhaps the least controversial compared to that of Japan, Germany, India, or even any country in Africa, which lacks consensus about who should represent the continent. Were the UN General Assembly to vote on permanent Brazilian membership in the UNSC alone, it would probably gather ample support with very few discordant voices. Yet Brazil will only enter the Council if the world can agree on a reform package that includes other countries, most notably two African countries. Convincing African nations that asking for veto power is unrealistic is only one of the myriad challenges that need to be addressed. And above all that, Brazilian foreign policy makers will have to convince a skeptical domestic audience that permanent UNSC membership is a goal worth pursuing.

Read also:

In Brazil, civil society and academia remain skeptical of the BRICS concept

Can Itamaraty engage civil society?

How many diplomats does an emerging power need?

Should Brazil have an embassy in North Korea?

Picture credit: AP