Perhaps one of the most important disagreements between realism and liberal theory in international relations is that the latter mandates a distinction among different types of states based on their domestic political structure and ideology.

While realists argue that the distribution of power in the international system is the main determining factor of a state’s behavior, liberals think that liberal democracies will comply more readily with the treaties that they sign and that these treaties are more likely to the subject to effective judicial enforcement at both the international and domestic level. Contrary to their illiberal counterparts, liberal judges also build a ‘transnational community of law’ through a readiness to cite one another’s opinions. Liberal democracies, in short, are better, more law-abiding citizens of the international community, and hopes for international order and more effective forms of international governance should be pinned on the global spread of democracy.

While most US and European foreign policy makers would affirm the question posed in the title, several thinkers around the world have criticized liberal theory. Some argue that liberals too readily assume that periodic elections ensure a genuine political choice or a free market of ideas. Liberals, they argue, have an uncritical and superficial view of democracy. For critical theorists (such as Beate Jahn), liberal theory is the oppressive voice of neo-liberal hegemony. Critics of the liberal approach point out that all states must be treated in an equal fashion, irrespective of their domestic political regime. If that is not the case, global law, they say, serves to authorize new hierarchies and gradations of sovereignty, to legitimate depredations of political autonomy and self-determination.

The most obvious incoherence of liberal theory is its incapacity to explain the behavior of the system’s supposedly liberal hegemon, the United States. Although liberals consider the United States to be he pre-eminent liberal state, it is difficult to contend that the U.S. approach to treaty obligations accords with liberal premises. The perception that international obligations may be ‘undemocratic’ helps explain many instances where the US has resisted or breached its international obligations – e.g. Congress’ hostility to paying UN peacekeeping or regular expenses. John Bolton’s famous ‘Should we take global governance seriously?‘ nicely sums up this argument. Interestingly enough, congressmen are partly reluctant to support international treaties because, to their mind, it reduces their power vis-à-vis the federal government.

Further, there is no evidence that the United States has historically distinguished between liberal and non-liberal treaty partners in terms of its readiness to enter into judicial forms of dispute settlement. In recent years, for example, the leading examples of US treaty obligations permitting ‘vertical enforcement’ by US domestic courts have not been treaties with other liberal nations but bilateral investment treaties (BITs), mostly with non-liberal states: The US government established the BIT program precisely to give US investors confidence in doing business where there was some concern about the stability of the foreign nation’s investment regime. By contrast, the OECD, a club of mostly liberal states, has long struggled to establish a multilateral agreement concerning investment issues. Paradoxically, one could argue that OECD members failed because they were liberal states responding to the pressure of domestic and supranational groups.

It seems clear, then, that all states, liberal or illiberal, are sometimes law-abiding on the international level, and sometimes not. Are liberal states at least more likely to act in accord with liberal tents? The evidence in mixed, and few studies are able to pinpoint regime type as the sole determining factor of whether a state obeys international law. Rather, liberal states at times have an easier time complying with many international treaties at least in part because the agreement reflected more of their own preferences, or was similar to already existing domestic law. Regarding the WTO, for example, there is no evidence that non-liberal regimes are more likely to fail to comply with a panel judgment once issued.

The perhaps most problematic aspect of liberal theory is its ambiguity regarding relations between liberal and non-liberal states. Critics argue that liberal theory is quite illiberal in that respect, reluctant to include non-liberal actors into governance structures even if that makes these structures more democratic.

Yet particularly at a time when a non-liberal state is poised to turn into the world’s largest economy and must be included, for better or worse, into all important international decision-making processes to address international challenges, creating a new iron curtain between liberal and non-liberal states seems unhelpful. China’s recent announcement to create an ambitious cap-and-trade system to combat climate change is yet another hint that even authoritarian regimes — as despiccable as they may be — can play an important role in global governance and the contribution of global public goods.

This does not mean that democracies should be indifferent to illiberal practices abroad. There is little doubt that citizens are better off in democratic countries, and it is highly preferable to live in a democracy than in an autocracy. Yet it is not clear whether democracies are really better global citizens than autocracies.

Read also:

South Africa’s BRICS membership: A win-win situation?

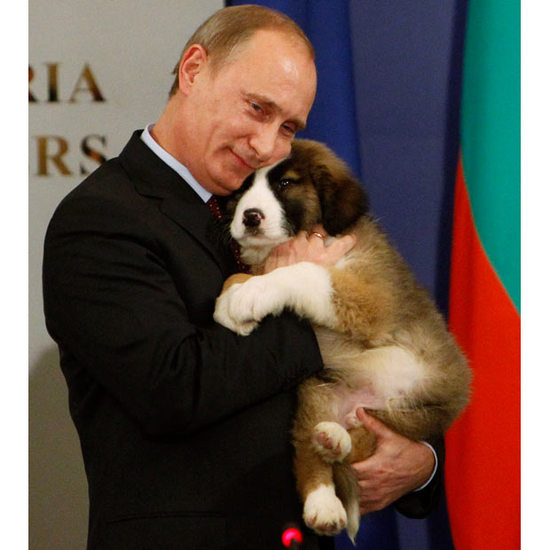

Photo credit: Reuters