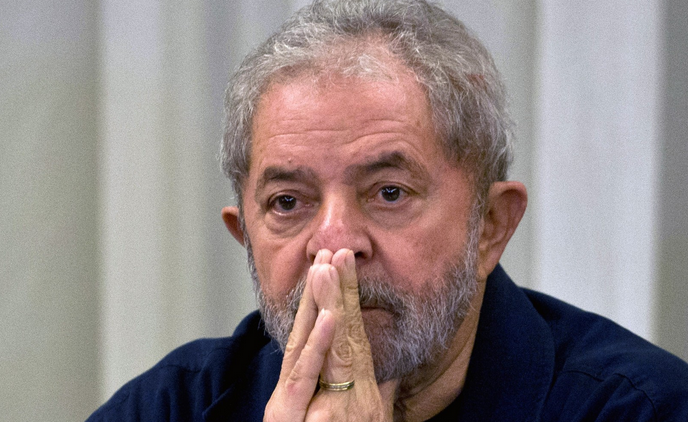

Since leaving office four and a half years ago, Brazil’s ex-President Lula da Silva has been, along with Bill Clinton, one of the world’s most popular former leaders, frequently speaking at international high-level conferences and causing aspiring politicians to try to emulate his success formula. Lula adroitly used the years after leaving power to spread the attractive narrative about how Brazil not only grew economically when most of the rest of the world was in crisis, but how he also oversaw one of the most remarkable reductions in poverty in recent history. Equally important, Lula dramatically enhanced Brazil’s visibility around the world, questioning established powers’ capacity to control and dominate the global agenda. Like few others, he stood for the growing trend of multipolarization and a more prominent Global South.

“The government”, Lula famously said in an address to diplomats in 2003, “has made a political decision to insert Brazil into the world as a major country, a country which likes to respect others but at the same time a country which wants to be respected.” Lula went on:

We will not accept any more participating in international politics as if we were the poor little ones of Latin America, a ‘little country’ of the Third World, a ‘little country’ which has street children, which only knows how to play football, and only knows how to enjoy carnival. This country does have street children, has carnival, and has football. But this country has much more. This country has greatness. . . . This country has everything to be the equal of any other country in the world. And we will not give up on this goal.

While all this was only possible due to a unique constellation of crisis in the West and strong Chinese demand for Brazilian commodities, the former President skillfully used this window of opportunity to strengthen Brazil’s global economic and political role, even though several of his greatest foreign policy initiatives (such as his attempt to mediate between Iran and the West) failed.

Recent developments, however, cast a pall over the former President’s legacy. The arrest of Marcelo Odebrecht, president of Brazil’s largest construction company, is significant because the company played such a crucial role in Lula’s strategy to internationalize Brazilian businesses — both in South America and in Africa, two regions the former President prioritized. Not only is Odebrecht tasked with the implementation of several important infrastructure projects that form part of the South American Integration Initiative (IIRSA), but it also has the primary responsibility for most of the 2016 Olympic Games infrastructure in Rio de Janeiro, a symbol of Brazil’s rise. Odebrecht accounts for nearly three quarters of infrastructure built by Brazilian companies abroad. Peruvian prosecutors plan to visit Brazil this month to gather evidence of bribery on a transcontinental highway project. Reuters reports that Ecuador opened audits of Odebrecht’s contracts, even though Odebrecht stressed they are part of a routine. Colombia’s vice president warned that the company could be banned from public bids for decades.

In addition, federal prosecutors in Brazil launched a criminal probe into whether Lula has been involved in influence peddling on behalf of Odebrecht, a move that made international headlines. Lula Is Supporting Corrupt Companies to Do Corrupt Business Abroad titled Foreign Policy, the same magazine that had called Celso Amorim the “world’s best foreign minister” in 2009. Finally, stagflation at home has strengthened opinions of the those who argue that Brazil’s current malaise is at least partly due to President Lula’s unwillingness to implement structural reforms during his second mandate, a move to assure the election of Dilma Rousseff, his chosen successor.

Several former leaders have faced investigations — such as Jacques Chirac, Nicolas Sarkozy, Tony Blair, Helmut Kohl and Bill Clinton — and it would be premature to announce Lula’s fall from international grace. And yet, the episode underlines that Lula’s definitive legacy remains yet to be written, and current developments may affect the former President’s place in history. The fact that Lula’s global reputation is in flux was summarized in one recent tweet by João Augusto Castro Neves, the Eurasia Group’s Latin America director, who, commenting on the article “Is Tsipras the New Lula?“, wrote:

Confusing comparison. Which one? Leftist Lula, Pragmatic Lula, charismatic Lula, hubris Lula, afraid to go to jail Lula?

If Lula were to be convicted, there is a risk that observers both at home and abroad switch from uncritical admiration to wholesale rejection. Both perspectives overlook important nuances. For example, Lula’s decision to bet on a small number of national champions now turns out to have been risky, market-distorting and prone to facilitate intransparent practices that may hurt Brazil’s national interest. At the same time, the former President’s assertive foreign policy and diplomatic expansion — symbolized by the growing number of Brazilian embassies around the world and more frequent travel — has generated substantial benefits, and it is all the more tragic that his hand-picked successor has lacked the interest or capacity to emulate Lula’s verve in this respect.

Read also:

How Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula worked together to woo George W. Bush

Brazil at the Eye of the Storm: Lula, Zelaya and Democracy in Central America

What would Lula’s return mean for Brazilian foreign policy?

Photo credit: El País, NELSON ALMEIDA (AFP)