Shanghai’s current stock market turmoil has left the many observers wondering about short-term implications for the global economy. Looking beyond immediate worries, two issues are worth noting. First of all, the current crisis is an unmistakable sign that the Post-Western World is already a reality: Two decades ago, a plummeting stock market in the global economy’s periphery would have hardly caused global tensions. Today, by contrast, the saying “When China sneezes, the world catches a cold” seems remarkably fitting. After all, a staggering 38% of global growth in 2014 came from China, and 120 countries trade more with China than with any other country.

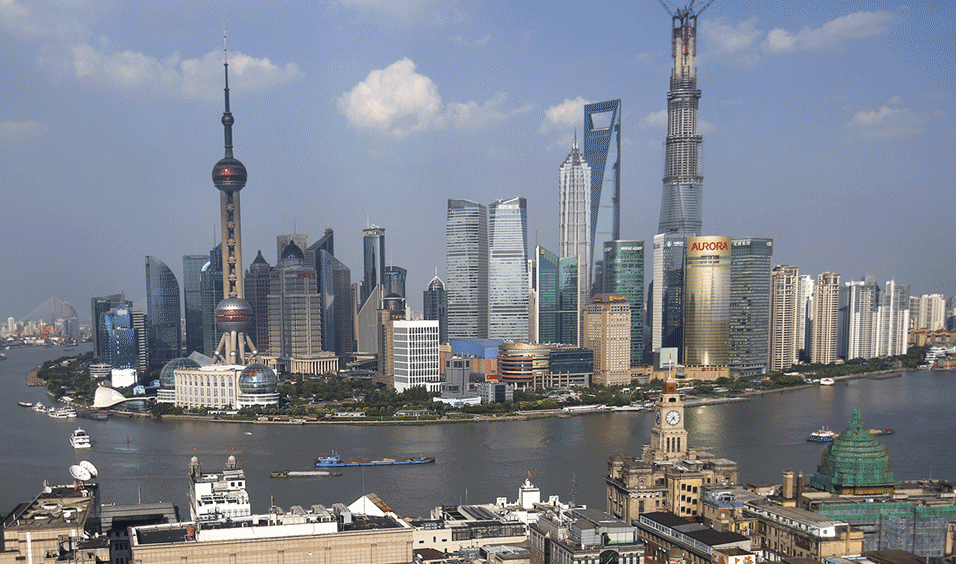

Secondly, the current crisis adds an interesting twist to one of the Chinese government’s most ambitious and fascinating strategies, which symbolizes the extent to which China is willing to alter global structures: To turn Shanghai, a regional also-ran behind other geographically close cities like Hong Kong, into a global financial center capable of challenging New York and London, the world’s only truly global financial centers. According to China’s State Council, this should be achieved by 2020.

Financial centers concentrate enormous economic power, and being home to one is seen as crucial to complement Chinese efforts in the realm of trade expansion and military modernization. Put differently, a global power cannot do without a global financial center.

As Kawaii explains,

A regional center can grow to function as a global financial center if it offers deep and liquid financial markets for global players – in addition to national and regional players; becomes a hub for global financial information; has a reservoir of highly educated and well-trained professionals (for investment banking, law, accounting, and information and communication technology (ICT); provides a conducive, responsive regulatory environment; and ensures economic freedom supported by unambiguous legal certainty.

China’s challenge, thus, is a complex one that involves not only the set-up of a clear regulatory framework, but also attracting global talent from around the world, which requires turning Shanghai itself into an attractive city. Considering how low Chinese cities tend to rank in the global quality of life indexes (as virtually all urban centers in developing countries), the Chinese government may have to undertake profound reforms to generate the momentum necessary to make young talents prefer Shanghai over New York, Zurich, Singapore, or other financial centers around the world.The government is considering lowering income tax for financial staff to become more attractive, particularly since income tax in Hong Kong is as low as 15%. Considerable investments in education, such as the Advanced Institute of Finance at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, are meant to help enhance the city’s still insufficient intellectual infrastructure – after all, banks still prefer Singapore and Hong Kong due to their larger talent pool — another area in which rich countries almost always beat poorer ones. If the Chinese government were ever to experiment with greater free speech, they may start in Shanghai, as censorship is unlikely to help bring international talent to the city. Anecdotal evidence suggests that most executives in finance from around the world would ask for substantial pay rises to accept a posting in mainland China, even though Shanghai offers a far more comfortable life style than Beijing or Chongqing.

China’s objective to turn Shanghai into a global hub is intimately tied to internationalizing the yuan, creating the China International Payment System (CIPS) and the establishment, in 2013, of the Shanghai Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ), which is seen as the Chinese government’s most innovative experiment. Initially the first free trade zone on the Chinese mainland, it has already led to three additional free trade zones, in Fujian, Guangdong and Tianjin. It is in these zones – and primarily Shanghai – that the Chinese government is set to conduct liberal experiments, not only regarding trade, yuan convertibility and interest rate systems, but also regulatory issues concerning joint ventures in the financial sector. Indeed, full convertibility of the yuan would be a requirement for Shanghai to begin to rival the existing financial centers. Before that, any such talk seems far-fetched.

In addition, the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE) launched, in 2014, a global trading platform in the city’s pilot free trade zone, a move meant to challenge the dominance of New York and London in gold trade and pricing – considered to be of great strategic importance. China has recently turned into the world’s leading importer of gold, and the SGE is the world’s largest trading platform for physical gold. However, Shanghai does not yet rival London or New York in its capacity to influence gold pricing. It ranks fourth worldwide for global gold transactions, just ahead of Dubai which is in fifth place. Too increase Shanghai’s attraction, foreign investors who are not legally established in China can now trade gold in the country. For China, a one-kilogramme yuan-denominated gold index could be useful to favour its own consumers and protect them from other foreign-currency denominated indexes, which Beijing might argue are prone to manipulation, or favour “Western interests”. Shanghai is also seeking to establish pricing benchmarks for a number of other commodities, most importantly oil.

Shanghai’s success in becoming a global financial center will ultimately depend on a large number of factors, not at least China’s overall economic trajectory. Provided that 5% growth can continue over the coming years, the State Council’s ambition do not seem completely unrealistic, even though they are still unlikely to be fulfilled in time. Shanghai’s advantage is, without a doubt, its role as the financial hub of what will be the world’s largest economy, even though a lot of financial power is still concentrated in Hong Kong and Beijing. That does not mean, of course, that Shanghai may rival the importance of London and New York in their entirety. New York and London have been central to the process of globalization over the past two centuries, and even if Shanghai were to seriously rival their financial capacity, the former two will remain cultural fixtures on a global scale for decades to come, and a magnet for artists and leading thinkers that China will struggle immensely to emulate.

London’s continued dominance is a case in point: Despite the expansion of the US economy, adverse impacts of WWI and the gradual decline of the British empire and economic prowess, New York never fully succeeded or overtook London as a global financial center. This shows that a financial center can sustain its strength even though its economic hinterland – in this case, Great Britain – no longer plays a key role in the global economy. China’s economic growth alone will therefore not be enough for Shanghai to replace existing global financial centers.

The idea of turning Shanghai into an international financial center is far from revolutionary – rather, in the eyes of China, it is about reestablishing the city’s key role it held as early as the 1920s and 1930s, when it was known as “Paris of the East”. Yet today’s ambition is still more than merely copying the past, and policy makers in Beijing are interesting in more than merely hosting the world’s most important stock exchange. Rather, they want Shanghai to be the place where the leading minds of the financial world gather to develop the ideas that will shape global finance for decades to come. Simply put, Shanghai’s role as financial center would allow it, the Chinese government hopes, to become the world’s leading agenda-setter in global finance. Considering that China will most likely be the world’s largest economy by then (China today represents about 15% of the global economy), a decentralization of financial power and a more diverse, geographically evenly spread allocation of decision-makers in the area is to be welcomed. After all, London and New York are far too homogeneous and similar to be able to act on behalf of a far more diverse global financial landscape.

Yet following reforms in Shanghai is important for another reason: It is likely to serve as a blueprint for the rest of China once the government feels safe to slowly release its grip on the country’s financial system.

Read also:

BRICS: Time to create an OECD-type structure?

Photo credit: Carlos Barria (Reuters)