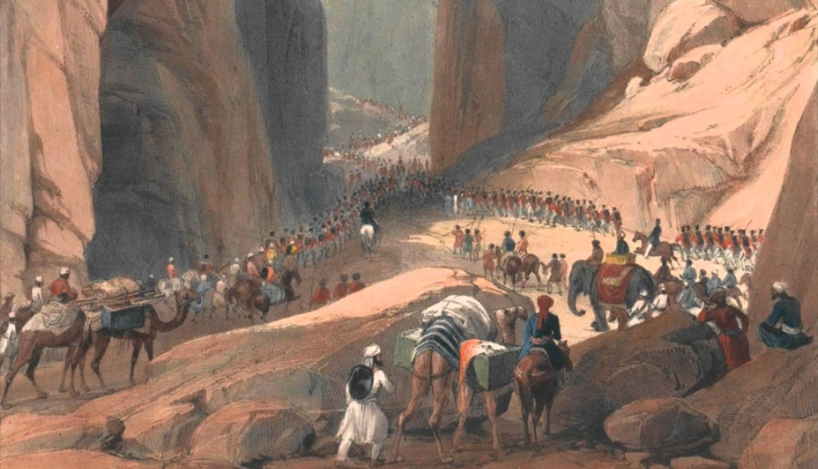

The Empire’s last stand: British troops during their humiliating retreat from Kabul in January 1842. Of the over 4,000 soldiers and over 10,000 camp followers, only around 100 survived as they crossed the Khyber Pass.

——-

Book review: Return of a King: ‘The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42′ by William Dalrymple. Vintage, 2014. 560 pages. $ 15.92 (paperback, amazon.com)

Published in: Projeto História, São Paulo, n. 57, pp. 361-367, Set.-Dez. 2016

——-

The story of the first British invasion of Afghanistan from 1839 to 1842, which would later be called the First Afghan War, is well known. Needlessly worried about growing Russian influence in Central Asia, a potential base from which to attack India, the jewel in the crown of the British Empire, policy makers in London decided to remove Dost Mohammad Khan from power in Kabul, replacing him with Shah Shuja, who was thought to be more pro-British and who would act as a client to the Indian Raj, against Russian interests. This move was part of the so-called ‘Great Game’ (known in Russia as the ‘Tournament of Shadows’), fired up by Russophobia among British foreign policy makers, creating an Anglo-Russian rivalry which would change the region’s geopolitics forever — even though it could have probably been avoided altogether, preventing the deaths of thousands of Afghans.

As so many major powers after them, the British underestimated the Afghans’ capacity to resist and fight against their occupiers. Holding on to Afghanistan proved too costly, and after locals murdered the British envoys William Macnathen and Alexander Burnes in 1841, the occupying troops opted for withdrawal, during which they suffered one of their worst military defeats in the history of the British Empire. A few months later, a British “retribution army” returned, for no other purpose than to wreak havoc across Afghanistan, committing war crimes in the process. Two weeks later, the British left again. Dost Mohammad Khan, the man London had sough to unseat, returned to power. While William Dalrymple’s Return of a King does not fundamentally question mainstream interpretations of the West’s first encounter with Afghan society, the analysis relies on an unprecedented amount of primary sources, including many letters written at the time, as well as epic Afghani poetry, that turns the book into the most sophisticated and engaging account of this remarkable episode of Asian history.

Afghanistan, a country of rugged mountains, cold winters, hot summers and few natural resources, mattered little to the British. Rather, Afghans were mere pawns on the chessboard of Western diplomacy, which explains why leading British envoys rarely showed any serious interest in Afghan culture — contrary to Indian or Persian culture, which, at least initially, was admired by many British officers.

The book is particularly good at showing how personal rivalries within the British imperial bureaucracy were crucial as the world’s foremost power stumbled into an entirely unnecessary conflict. Though Dalrymple argues that defeat was not inevitable, his account underlines how better judgment could have solved London’s problems in a far less costly manner. Indeed, rather than imposing Shah Shuja by force, the British could have struck an alliance with Dost Mohammad. After all, the Afghan leader was clearly more inclined to work with the British than with Russia.

What is perhaps most shocking is that the British possessed the knowledge that could have prevented disaster. The Empire’s greatest Afghanistan expert, Moutstuart Elphinstone pointed out that success was impossible: “… I have no doubt you will take Candahar and Cabul and set up Shuja…. but for maintaining him in a poor, cold, strong and remote country, among a turbulent people like the Afghans, …, seems to me hopeless. If you succeed … you will weaken your position against Russia. The Afghans were neutral and would have received your aid against invaders with gratitude — they will now be disaffected and glad to join any invader that will drive you out.” (p.116) It is a lesson the Russians should have learned prior to their invasion in the 1980s, a catastrophe that contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Due to its wealth of contemporary sources, Return of a King provides the reader with a lot of insights of day-to-day life in the region at the time. Dalrymple provides detailed accounts of the complexity of Afghanistan’s tribal rivalries, their influence on politics, and how they ensnared both the British of the 19th century and NATO forces today.

Just like in 2001, conquering Afghanistan was relatively easy in 1839 (even though hundreds of sepoys died in the march towards Kabul), allowing the British to restore Shah Shuja to the throne. Yet Afghans soon saw Shuja, who had ruled Afghanistan thirty years earlier, as a puppet of the infidels. As the British realized how unpopular their presence and the leader they had reinstated was, Lord Auckland took the fatal decision to allow British soldiers to bring their families — a clear sign to the Afghans that they were about to suffer the same fate of permanent occupation as Hindustan. They were right: Imperial overconfidence soon led to informal discussions about moving the summer capital of the Raj from Simla to Kabul, which would have implied the permanent annexation of Afghanistan.

A foreign troop presence in Kandahar and Kabul produced predictable problems, ranging from the spread of prostitution to inflation and food shortages. Even though there were clear signs of trouble, many British troops were removed to prepare for the Opium War in China. When payments to loyal tribes were cut, the occupiers’ fate was sealed, as was that of Shah Shuja, whom Afghan’s called “the Foreigners’ King”. The final weeks of the British troops in Kabul are told in a masterly way, showing how impending disaster led officials to commit ‘idiotic mistakes’, as Shah Shuja put it — like retreating in the midst of the winter across the Khyber Pass.

In retrospect, it is no surprise that the world’s most powerful Empire could not accept such humiliation without responding with senseless vengeance. The army led by General Pollock, which returned to Afghanistan in the following spring, had the sole purpose to cause immense suffering among Afghanistan’s civilian population, indiscriminately killing farmers, cutting trees and destroying the great Char Chatta covered bazaar on the grounds that it was where Macnaghten’s headless trunk had been put on display after his murder in December 1841. For Afghans, it was a sign of British weakness, with one writer quoting a fitting proverb: “When you’re not strong enough to punish the camel, then go and beat the basket carried by the donkey.” As the author puts it, “it was one of the many ironies of the war that while British interest in promoting commerce between India and Afghanistan had been one of the original motives for sending Burnes on his first trip up the Indus, the final act of the whole catastrophic sage was the vindictive demolition of the main commercial center of the region.” (p.308)

Interestingly enough, Afghan victory against the British provided the historical material necessary for national mythmaking, which helped create a sense of nationhood in a region that, prior to British invasion, largely saw itself as a disparate tribal community loosely tied to the Persian empire.

Invading Afghanistan was a terrible and costly mistake, of course, and the book describes incompetence, stupidity, arrogance and vanity on such scale that make the reader wonders how the British could ever manage to create an Empire in the first place. Granted, fears that Afghanistan could threaten stability in India were based on some historical evidence. Dalrymple describes invading Hindustan as a “time-honored Afghan solution for cash crises” (p.35), which made a clash with the British inevitable once they occupied the subcontinent. And yet, paradoxically, it was British activities along the Russian border in Central Asia that first got St. Petersburg interested in the region. As the author points out, “As so often in international affairs, hawkish paranoia about distant threats can create the very monster that is most feared.” (p.81).

The parallels to NATO’s decision to invade Afghanistan are so painfully obvious they sound like the chorus in a Greek tragedy. Hamid Karzai, who would be installed by the West in December 2001, shares the same tribal heritage as Shah Shuja. The Shah’s principal opponent was the Ghilzai tribe, which today make up the bulk of the Taliban’s foot soldiers. Both the British enemies back then, led by Dost Mohammad and today invoked jihad to expel the foreign occupiers. The site of the British cantonment outside Kabul in 1839 is today occupied by the US Embassy and NATO barracks. The debates between British officials during the occupation in the 19th century are eerily similar to contemporary discussions. The author describes how, after a British diplomat in 1840 was shocked to witness the stoning of a local woman who confessed to adultery, a colleague warned him that “we are not in Afghanistan to nation-build or to encourage gender reform.” (p.142). In the same way, London’s attempts to build up a professional army to maintain stability in Afghanistan remains NATO’s greatest challenge today.

Now, as then, there are many doubts that NATO’s 15-year long occupation will stabilize Afghanistan (then known as Khurasan). Failure is a real possibility today because, just like in the 19th century, Afghanistan is a mere side show for Western policy makers, and political support for a long-term commitment is nonexistent. As London considered the China expedition more important, the author writes, “Macnaghten [who had gone to Kabul as envoy] would never have the troops or the money he would need to make Shah Shuja’s rule a success.” Having the larger army does not guarantee success unless there is strong public support at home.

Diary entries by British officers at the time could be mistaken for memos produced by contemporary policy makers: “Success in battle in Afghanistan”, Elphinstone wrote in 1809, “was rarely decided by straightforward military victory so much as by successfully negotiating a path through the shifting patterns of tribal allegiances.”

The first Anglo-Afghan War was the opening chapter of the West’s unfortunate relationship with Afghanistan, a tragedy going on until today. Dalrymple’s book comes too late for Soviet leaders who foolishly hoped to install a puppet regime in the 1980s, or for US leaders who believed they could transform Afghanistan in a liberal democracy after the attacks of September 11th 2001. Given that Afghanistan is set to maintain its odd combination of vulnerability and resilience, major powers will continue to be tempted to control this strategically crucial region. Perhaps one day, a decade or two from now, Chinese policy makers, keen on expanding their influence in Central Asia, will read Return of a King and think twice before repeating the mistake that so many great powers have made before them.

Read also:

Temptations of the West: How to be modern in India, Pakistan and beyond

Book review: “Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition” by Nisid Hajari

Book Review: “After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire” by John Darwin

photo credit: Photos.com/Jupiterimages