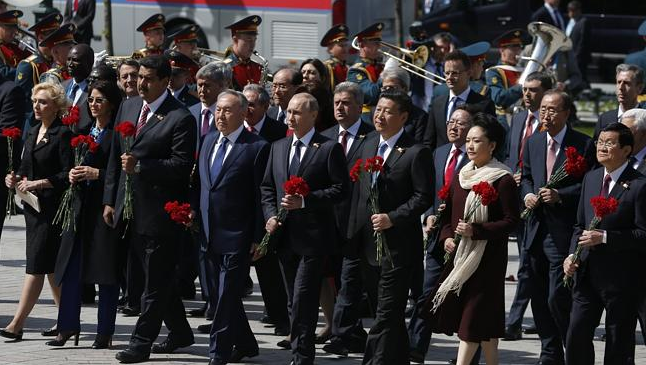

Friends in need are friends indeed: In 2015, Maduro (third from left) marches with Putin (middle) to celebrate Russia’s military victory in 1945. The festivities took place a time when Moscow faced growing diplomatic isolation over its role in Ukraine.

————

While many analysts from around the world continuously predict the chavista regime’s imminent demise, there are several reasons why Maduro can be expected to remain in power for now. The opposition is weak and divided, and the armed forces are making unknown riches from controlling the distribution of food and medicines, having little interest in changing the status quo. Paradoxically, increased scarcity boosts their gains, so they have no interest whatsoever to get the economy back on track. With many unwanted troublemakers migrating to Colombia, Brazil, the United States, Argentina and Spain, and violence against protesters continuing unabated, the days of mass protests are unlikely to continue for long.

Externally, the situation remains equally benign. A growing number of governments in the region have openly condemned Venezuela’s authoritarian turn — among them Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Paraguay — but stalwart allies in La Paz, Managua, Havana and the Caribbean assure that Venezuela’s suspension from Mercosur will remain the exception. Caracas won’t face much pressure in UNASUR or the Organization of American States (OAS). The United States is unlikely to impose an oil embargo as it would hurt US-American consumers by driving up the oil price at gas stations, and Donald Trump’s ill-conceived comments about a possible military option help Nicolás Maduro’s narrative that foreign meddling is the real reason for Venezuela’s economic crisis. Even if the US imposed an oil embargo, ending its daily purchases of around 700,000 barrels a day, Venezuelan oil would find buyers in Asia.

Yet none of the above would be sufficient if both Beijing and Moscow did not provide solid economic support to the Maduro regime. After having invested billions of dollars in Venezuela, both the Chinese and the Russian governments have little interest in seeing a newly empowered opposition question the validity of their oil deals, exposing Moscow and Beijing to a legal quagmire. China, in particular, can therefore be expected to continue supporting Maduro’s government financially. Over the past few years, China has lent over $60 billion to Venezuela, most of which it pays back with oil shipments, and none of which includes policy conditions. The support provides privileges for Chinese companies in key sectors of the Venezuelan economy such as cars, telecommunications, appliances, and oil drilling.

Last year, when the Venezuelan government came relatively close to defaulting, Caracas pocketed half a billion dollars from the Russian state-run company Rosneft, which increased its stake in the Petromonagas joint venture. It is now one of the key investors in energy in Venezuela.

As Marianna Parraga and Alexandra Ulmer write,

Rosneft currently owns substantial portions of five major Venezuelan oil projects. The additional projects PDVSA is now offering the Russian firm include five in the Orinoco – Venezuela’s largest oil producing region – along with three in Maracaibo Lake, its second-largest and oldest producing area, and a shallow-water oil project in the Paria Gulf, the two industry sources told Reuters. In a separate proposal first reported by Reuters last month, Rosneft would swap its collateral on 49.9 percent of Citgo – the Venezuelan owned, U.S.-based refiner – for stakes in three additional PDVSA oil fields, two natural gas fields and a lucrative fuel supply contract, according to two sources with knowledge of the negotiations.

Yet the partnership goes far beyond oil. As Thomas O’Donnell points out,

Between 2012 and 2015, Russia sold $3.2 billion in arms to Venezuela, making it the number-two buyer of Russian arms globally during that period. And in October 2014, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro pledged another $480 million to purchase 12 Sukhoi-30 jetfighters and to upgrade existing Sukhois in the Venezuelan fleet.

In addition to economic gains, however, Russia’s strategy also assures Venezuela’s support in multilateral fora and on the international stage in general at a time when Moscow continues to suffer from diplomatic isolation. An episode two years ago makes this clear: On May 9, 2015, Russia celebrated its victory over Nazi Germany 70 years earlier with the biggest parade of its kind since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The event, however, took place the midst of a delicate geopolitical moment, with most Western leaders — including Barack Obama, David Cameron and Angela Merkel — declining the invitation to join the festivities due to Russia’s controversial role in Ukraine. Until the final days before the event, Russian diplomats urged leaders from around the world to come, signaling how much a strong international presence meant for a leader who wanted to show his population that he was not isolated on the international stage.

Except for Brazil, the BRICS countries were represented by their respective leaders (the fact that Dilma Rousseff canceled in the last minute to attend her physician’s wedding caused consternation in Moscow and affected the bilateral relationship for some time). Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sissi and Cuba’s President Raul Castro also attended. And, of course, Nicolás Maduro, who lauded Russia’s leader repeatedly prior to and during the trip. A year later, he went further still, and created a new peace prize in honour of former socialist leader Hugo Chavez – and awarded it to Vladimir Putin. The award was given on the same day the Nobel Peace Prize was presented to Juan Manuel Santos, President of Colombia — and was widely commented on in the Russian media.

As Brazil’s President Michel Temer plans to discuss Russia’s role in Venezuela during the upcoming BRICS Summit in Xiamen, he must keep in mind that today Caracas is seen, by Moscow, as one of Russia’s most reliable allies.

Read more:

How Venezuelan Refugees Are Surviving in Brazil

Why Venezuela will not look like Cuba (or North Korea)

Why does Brazil’s Workers’ Party still support the Maduro regime in Venezuela?