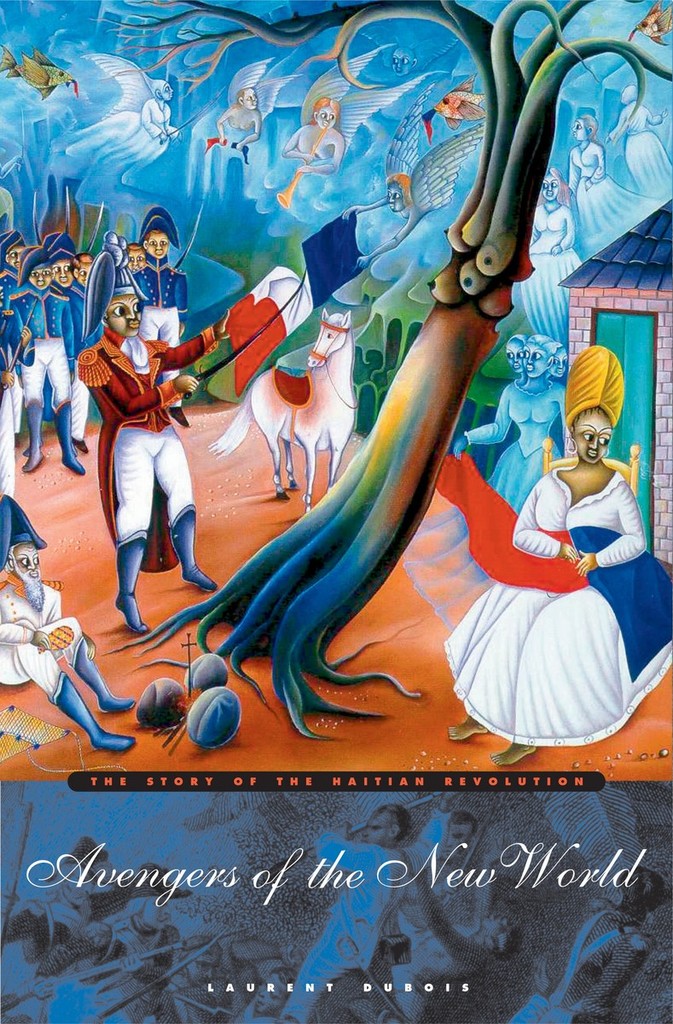

Book review: Avengers of the New World. The Story of the Haitian Revolution. By Laurent Dubois. Harvard University Press/ Belknap Press, 2005. 384 pages. US$ 25.75 (paperback, amazon.com)

——–

“I swear that you will see all my blood flow before I consent to your freedom, because your slavery, my fortune, and my happiness are inseparable.”

White slave owner in Port-au-Prince, 1792

Few countries in the world have suffered more than Haiti — a nation generally associated with poverty, violent political instability and outside intervention. Indeed, Haiti remains one of the poorest countries in the world, according to the World Bank, with a GDP per capita of $846, making the average Haitian ten times poorer than the average Brazilian.

Yet Haiti’s history is also filled with profoundly inspiring episodes, which are remarkably absent from mainstream accounts of global history. Saint-Domingue, the most profitable colony in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, saw the largest slave revolution in the history of the world, as well as the first and only successful slave revolt in the Americas. Starting in 1791, when thousands of slaves rose up against their French masters, Haiti sent shivers down the spines of slave holders across the Western Hemisphere, who feared the event could upend master-slave relations permanently. From the United States, the Caribbean to South America, black populations heard of the black revolution. In Rio de Janeiro in 1805, soldiers of African descent wore coins with portraits of Haitian revolutionary heroes.

Initial victory proved short-lived. British and Spanish forces attacked the colony, and Napoleon sought to reconquer the country (he succeeded in Guadeloupe, where the population was enslaved one more time). The independence of Haiti in 1804, after a war that had killed more than 100,000, reshaped the Atlantic world by leading to the French sale of Louisiana to the United States and the expansion of the Cuban sugar economy. For the first 50 years of Haiti’s existence, the United States did not recognize it as a legitimate and independent nation. US President Thomas Jefferson suggested, in a conversation with the French Ambassador in Washington, cooperation between the United States, France and Great Britain to “confine this disease to its island”, by “not allowing the blacks to own ships.” In 1803, Napoleon echoed such views to his general Leclerc before sending him to violently crush resistance in Haiti: “Rid us of these gilded negroes, and we will have nothing more to wish for.” Henry Addington, the British prime minister, declared that the “interests of the [our] governments are exactly the same—to destroy Jacobinism, especially that of the blacks.”

Why was Haiti so important? As Laurent Dubois explains on the first pages of his fascinating account,

[Haiti’s independence] was a dramatic challenge to the world as it then was. Slavery was at the heart of the thriving system of merchant capitalism that was profiting Europe, devastating Africa, and propelling the rapid expansion of the Americas. The most powerful European empires were deeply involved and invested in slavery’s continuing existence, as was much of the nation to the north that had preceded Haiti to independence, the United States.

Economically, Haiti was a key player in the global economy: By the eve of the revolution, it was the world’s leading producer of both sugar and coffee. Haiti’s slave population was estimated to be half a million, compared to 700,000 in the United States. Haiti exported as much sugar as Jamaica, Cuba, and Brazil combined and half of the world’s coffee, making it the centerpiece of the Atlantic slave system, the author notes.

Just as importantly, events in Haiti were the most concrete expression of the idea that the rights proclaimed in France’s 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen were indeed universal. The majority of the population in Saint-Domingue (renamed Haiti after independence) was not only mainly constituted of slaves, it was also born in Africa, making it a precursor to the struggles for African decolonization. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that the Haitian revolution was as important in the history of human rights and democracy as the French revolution, precisely because assured these concepts would have a truly universal relevance (an idea rejected by most Europeans at the time). As the author aptly remarks, “we are all descendants of the Haitian Revolution, and responsible to these ancestors.” Yet paradoxically, Haiti is only rarely recognized as a relevant agent in the history of these very ideas, reflecting a broader pro-Western bias that rarely lends agency to non-Western peoples.

Dubois is a gifted storyteller, and excels in describing how tension rises in Haiti after the French Revolution. As abolitionist activity increased in Paris (with some prominent members such as the marquis de Lafayette and the comte de Mirabeau), slaveholders were profoundly worried that such ideas would reach slaves in the colony.

Avengers of the New World also helps the reader gain a more nuanced understanding of the many different groups vying for power ahead of the revolution — rather than merely white slave owners vs black slaves, Haitian society was made up of a myriad of subgroups (‘free people of color’, whites who owned land, whites who did not, blacks born in Africa, etc.), which created complex and temporary alliances, which are crucial to understanding why conflict continued even after independence. They contributed, however, to the very idea of revolution. As Dubois points out, the pre-revolutionary ”system of racial hierarchy, which most whites saw as necessary for the survival of the colony, was saturated with contradictions and dangerous fissures.” (p.70). When France’s National Assembly decided that “men are born and remain equal in rights”, slave holders in the Caribbean were so terrified that slaves in Haiti would rebel that in April 1790 local officials directed Le Cap’s postal director “to stop all arriving or departing letters that are addressed to mulattoes or slaves and to deliver these letters to the municipality.” Yet interestingly enough, the first conflicts did not break out between black slaves and white slave owners, but between whites and ‘free coloreds’ who demanded full citizenship. Quite remarkably, many ‘free coloreds’, were not opposed to slavery.

When rebellion spread among slaves, however, French troops were unable to resist for long. Dubois points out that, contrary to other failed revolutions elsewhere, many Haiti’s African-born slaves had significant combat experience from civil wars in Western and Central Africa, allowing them to withstand the much better-armed European soldiers. Some free people of African origin had served with the French colonial militia, providing the insurgents with crucial intelligence — even though the white elite desperately tried to create alliances with the ‘free coloreds’ against the rebellious slaves. Yet early on during the rebellion, though successful, signs emerge that independence would merely be a first step of many. Each grouping had very different motivations and goals, and hence, different expectations of what would happen next. As Dubois writes,

The insurgents of 1791 were enormously diverse—women and men, African-born and creole, overseer and fieldworker, slaves on mountain coffee plantations and sugar plantations—and carried with them many different motivations, hopes, and histories.

In early 1793, the war becomes an impossibly intricate game involving not only domestic forces, but also the British and Spanish empire, which by that point had declared war on France. With King Louis XVI executed in France, slaves began to join the French Republic, while white slave owners offered Haiti to the British. To make matters more complicated still, Spain was also seeking to recruit former slaves, eyeing a potential takeover of the colony they had lost a century earlier. The book’s constant back and forth requires some attention, but provides an acute sense of how confusing the conflict must have seemed to contemporaries.

In the book’s riveting final chapters, Dubois describes how the Haitian population achieved the unthinkable, defeating Napoleon’s army of 80,000 fighting men, carried across the Atlantic by fifty ships to reassert French control and to reestablish slavery. But just like so often in history, the occupiers were outfoxed and outlasted by the battle-hardened local population. Bonaparte was outraged: ““How is it possible that liberty was given to Africans, to men who had no civilization, who didn’t even know what the colony was, what France was?” It would be one of Napoleon’s most painful defeats, one he would regret as he lay on his death bed in St. Helena years later.

Desperate that France was unable to control, the island, Napoleon’s general Leclerc wrote in his letter to Paris: “Here is my opinion on this country,” he wrote to Bonaparte. “We must destroy all the blacks of the mountains—men and women—and spare only children under twelve years of age. We must destroy half of those in the plains and must not leave a single colored person in the colony who has worn an epaulette.” The only hope, the French commanders concluded, was to start again in Saint- Domingue with men and women imported from Africa who had never known “what it was to have broken the chains and won their freedom in the New World.”

Read also:

“Why Govern? Rethinking Demand and Progress in Global Governance” by Amitav Acharya (ed.)

China’s Second Continent: How a million migrants are building a new empire in Africa