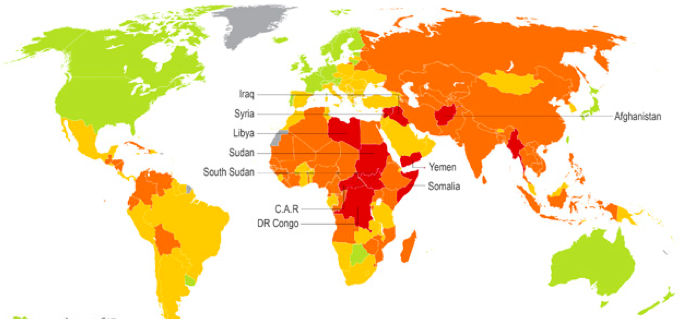

Maplecroft, a global risk and strategic consulting firm, assesses the risk of political instability.

———–

Political scientists often complain that internationally operating companies take key investment decisions purely based on economic data, while neglecting political risk. Executives generally believe it is so hard to quantify politics that it is usually left out of the equation altogether — or will be considered informally, i.e. via the famous “gut feeling.”

As Ian Bremmer and Preston Keat point out in The Fat Tail, perhaps the most important book on political risk,

A recent survey of executives on risk management in the financial services industry revealed that political risk was considered the least likely of all risk categories to be managed well. Geopolitical risk was also perceived as least likely to impact a corporation—and thus least likely to be included in a company’s risk management planning.

Indeed, many executives believe they are only rarely affected by political events that dominate the news, such as the civil wars in Syria and Iraq, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, or tensions between China and Japan. And yet, political risk covers far more than the risk of violent conflict in specific markets. In addition to geopolitical risk, the risk of terrorism, expropriation, corruption and changing regulatory policies can affect companies acting internationally.

Over the past years, there has been a growing notion that systemic political instability was becoming the “New Normal”. In 2014, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace asked its leading international affairs experts an intriguing question: “Every day seems to bring more bad news as global instability rages on. But is the level of turmoil really unique? Or does it just feel like it?” (Their brief responses can be read here, under the title “Is the World Falling Apart?” ).

Yet as frequent as civil wars and the like seem to be, and as much as they dominate the 24-hour news cycle, there are four more important trends that explain why a deeper understanding of political risk is bound to become more important in the coming years.

First of all, we are witnessing a notable rise of populism and nationalism both in the United States and in Europe- mature democracies that have usually rejected political extremes. Across the board, fringe candidates both on the left and on the right gain support from disillusioned voters who no longer trust or even hate the political establishment — possibly due to rising inequality and low economic growth. That increases the potential for protectionism and nativism, all of which negatively affect international business. In China and Japan, the rise of nationalism has an uglier dimension, with the potential to increase the risk of military conflict in the region. The rise of populists in the West explains why political risk analyses are no longer exclusively needed by companies that operate in unstable developing countries. Rather, whether Schengen survives or whether Great Britain leaves the EU (key issues with massive economic consequences) are, above all, political questions.

Secondly, the world’s economic growth is increasingly driven by emerging markets—countries with less defined rule of law, less well-developed institutions, and greater political volatility. While political change in Beijing would have mattered only to those multinationals with operations in China before, today it impacts the global economy as a whole. No single question affects the global economy more today than whether the Communist Party can manage China’s economic transition without a hard landing and without facing social tensions.

Thirdly, even though some had predicted its demise, state capitalism is as strong as ever, which makes understanding political trends important to assess the behavior of “national champions”, many of which are today amongst the world’s largest companies. Because several emerging powers, who occupy a growing share of the global economy, embrace state capitalism, its overall importance in global affairs is increasing. For example, Petrobras’ strategic decisions cannot possibly be understood without making sense of the PT government’s convictions and political pressures that explain laws (e.g., local content rules), which contributed to the profound crisis the company finds itself in. Its share value also depends on whether one believes that the Brazilian government would bail out Petrobras if necessary.

Finally, a post-hegemonic United States is far less capable of establishing and projecting rules and norms on a global scale than it used to. While possessing profound knowledge of political trends in Washington DC and London may have been sufficient in the 1990s, today multinational companies must be aware of dynamics in Beijing, Delhi, Brasília, Brussels and elsewhere and be able to take decisions regarding climate change, global regulatory policy, peace in Syria or cyber security. This does not mean that a multipolar world will be more unstable — rather, it means that, with decision-making power more spread out across the world, profound knowledge of politics in a growing number of countries is more important than at any time during the 20th century.

Despite the growing consensus that greater political knowledge is crucial to make sound investment decisions, many companies still struggle as to how to integrate them precisely. After all, as Nassim Taleb argues in The Black Swan, most political events that massively impact businesses — e.g., the revolution in Iran, end of the Soviet Union, and September 11 — were largely unpredictable. In The Fat Tail, Bremmer and Keat accept that black swans are a lost cause, but they argue that other aspects of political risk — regulatory changes, expropriation, coup d’états, corruption and so on — are predictable, and careful analyses can help companies quantify the risks and protect themselves. Several of those are set to become more important in the near future due to the reasons cited above.

Their book contains an extensive list of examples of how companies successfully dealt with political risk, mostly using scenario-building exercises to develop alternative plans. Still, while their book is an engaging read, those skeptical of including political risk analysis into their decision-making processes may not necessarily change their mind after reading it, for the book includes many anecdotes, but, ultimately, few concrete proposals. Still, it is a good introduction for those interested in the field.

Read also:

Why China is the greatest beneficiary of geopolitical events in 2015

Book review: “The End of Power” by Moisés Naím

Book review: “Taming American Power” by Stephen Walt

Análise de risco político: como as empresas multinacionais decidem onde e como investir?

Photo credits : maplecroft